It is hard to walk around Manchester without finding a few bees. They are everywhere. The mosaic floors of the Town Hall, planters, bins, lamposts. Even tattooed onto people. The bee was chosen as the symbol of Manchester to represent its productivity during the industrial revolution, and it remains a strong emblem of the city today.

So it figures that our collections must be chock full of bees too, right? Errr, no.

Sure, there are a few images here and there. We have some textile samples and shipper’s tickets (early trademarks) featuring bees. We also hold a collection of material relating to Boddingtons Brewery, which chose a barrel and two bees for its logo.

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

But beyond that, the collections are surprisingly short on bees.

Or are they? We may not have much in the collections featuring bees, but if you delve a little further, you can find a history of techniques and technology which have all developed thanks to the humble bee. In fact, over the years, bees have helped us with lighting, art, music, fashion, engineering, cosmetics, medicine, lubrication, cleaning and adhesives. How? Beeswax.

Bees secrete wax from their bodies and use it to build their honeycombs and to seal in their honey. Aside from having to brave thousands of angry bees, this wax is fairly easy to obtain and to process. Once you have removed the honey, the wax is boiled and strained to remove any debris, which is called slumgum.

Whilst we still haven’t found much use for slumgum, we have been resourcefully using beeswax for almost as long as we have been eating honey. In fact, the Science Museum holds a specimen of beeswax that was found in an Egyptian tomb dating back to 1500 BCE.

So here are a few of the items in our collections that demonstrate our wide usage of beeswax over centuries:

Light

Candles date back to the Romans, and the first recorded use of wicked candles is around 500 BCE. Candles in the middle ages were usually made from tallow (animal fat), but it was later discovered that beeswax made excellent candles that did not give off such an unpleasant smell. However, beeswax was expensive and the candles were therefore mainly used by the rich and by the church.

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

Fashion

The technique of wax resist dyeing is ancient. It developed in varying forms throughout the world, but traditional Indonesian batik used beeswax as it was readily available. The wax is applied in a pattern to fabric, which is then dyed. The wax resists the dye, so that when it is removed, the pattern remains in place.

The museum holds many examples of wax resist fabrics. The ones in our collection were mostly sold in Africa, and probably used a combination of beeswax and paraffin, but the technique and the design inspiration stemmed from the early batik methods.

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

Sound

Phonographs like this one were early forms of record players. The early machines used a needle that engraved the sound onto wax cylinders made of beeswax and paraffin. Early examples of these cylinders were soft, and wore out after only a few plays. They also all had to be recorded live, as there was no means to mass produce them. Later cylinders were harder and could be shaved down for reuse. Cylinders continued to sell until the 1910s, when they gradually declined in favour of flat vinyl ‘records’.

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

Medicine

Beeswax has been used in medicine for many years. The Science Museum holds several examples of anatomical wax models, used in the 18th and 19th centuries as a method of teaching. Bodies were difficult to obtain and to preserve long enough to teach students, so artists sought to produce accurate models, and would certainly have used beeswax in this process.

Beeswax has also been used in dentistry, for taking impressions of teeth and for fillings.

Adhesives

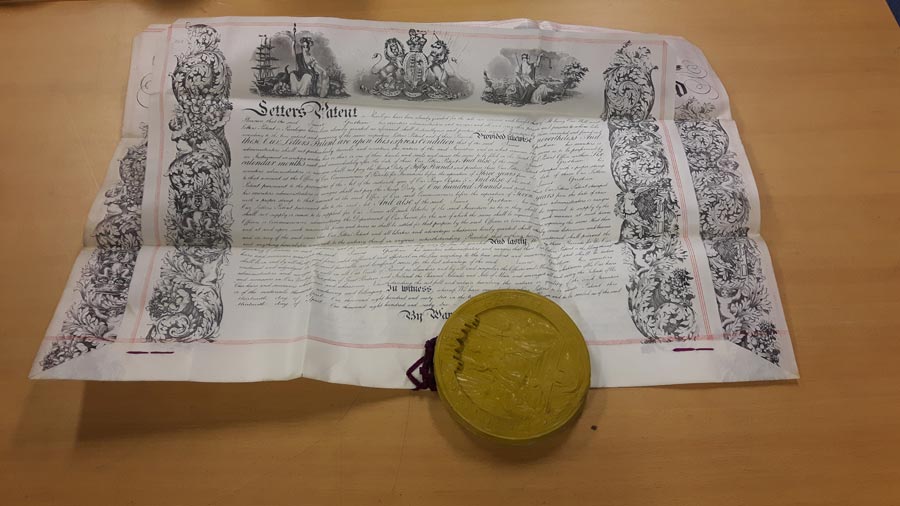

Wax was used from an early date to seal letters, because it hardens quickly and it was difficult to open letters without breaking the seal. In the middle ages, sealing wax was made of beeswax. Wax was also used to seal bottles and jars. Less expensive materials were later used, though beeswax continued to be used for large seals on public documents such as the one pictured below.

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

Art and engineering

In ‘lost-wax’ casting, an artist creates a wax mould of their object over a clay core. The wax is then surrounded by more clay. When the model is fired in kiln, the wax melts, leaving an inner chamber which can be filled with liquid metal. This then hardens into the finished object.

The process dates back to the Egyptians who developed the method using beeswax to make statues and jewellery.

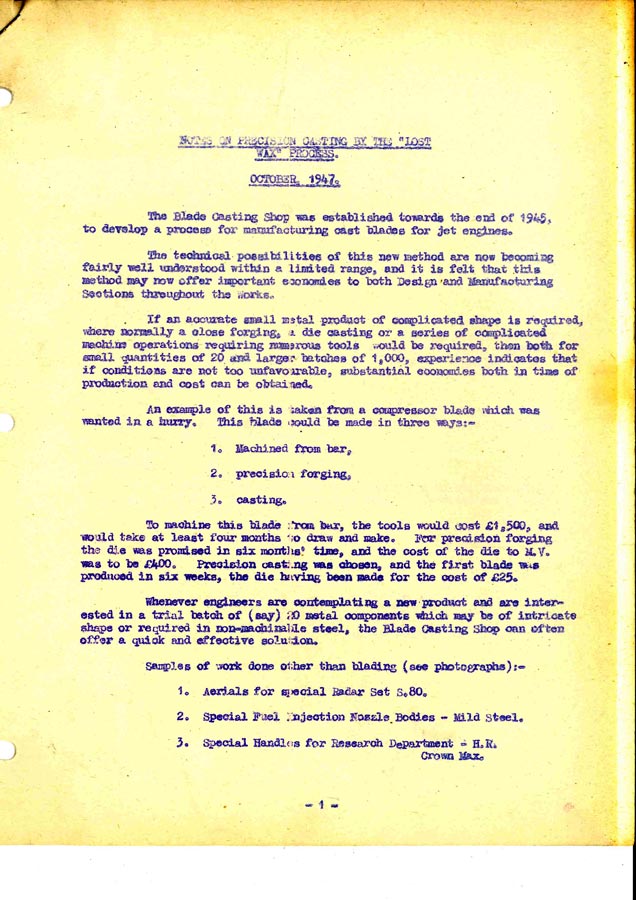

This report from Metropolitan-Vickers Electrical Co Ltd shows that the lost-wax technique has since been used for precision casting of engineering components. Though beeswax is unlikely to have been used in foundries, it was instrumental in the development of the process.

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

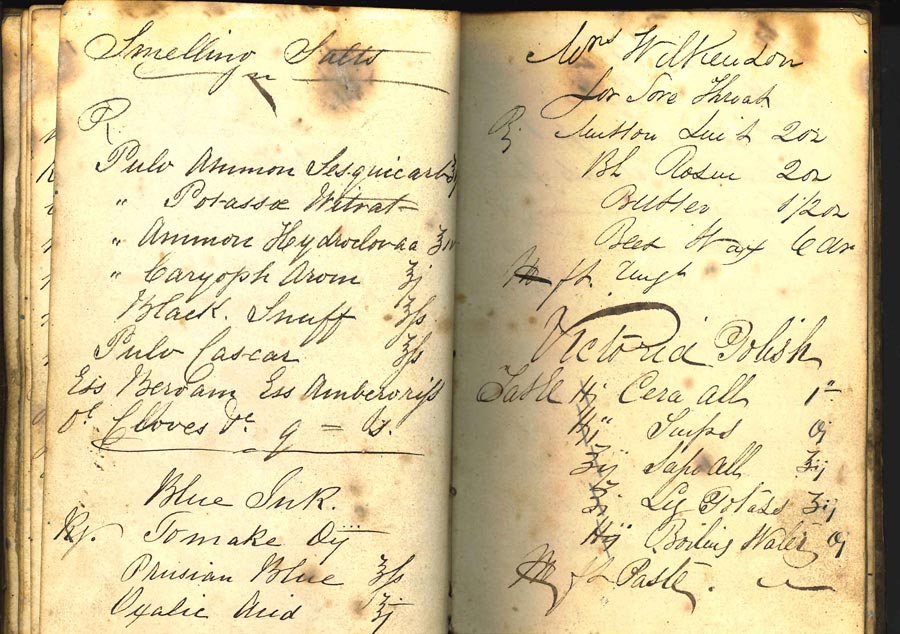

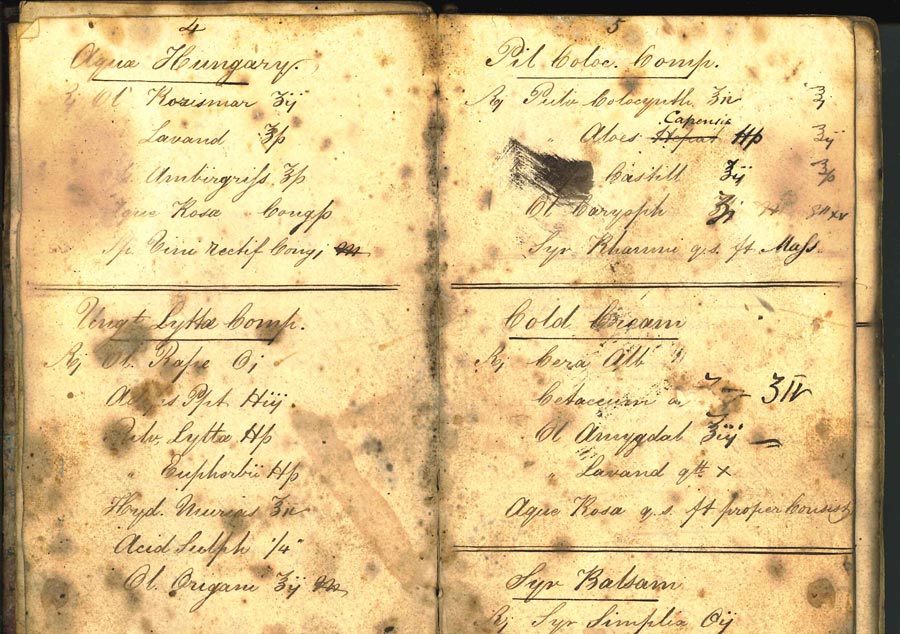

Cosmetics and homewares

Beeswax is non-allergenic, moisturising and is said to have therapeutic properties for skin healing. This makes it an ideal ingredient for cosmetics and it is used in products such as eye make-up, lip balm, moisturisers and hair pomades. Beeswax is also useful in cleaning products such as furniture polish, as it creates a protective barrier for wood.

This is not a new discovery—these extracts from an 1834 recipe book of an Eccles chemist show formulas for cold cream and Victoria polish, both using ‘cera alba’, the scientific name for beeswax.

The bee symbol for Manchester is a proud reminder of our industrial past and the strong community that built up around it, but these little insects have also contributed directly to innovations around the world. In lots of ways, bees really do represent this city—a city that may seem small and ordinary, but has actually changed the world and still has a sting in its tail.

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum