Please note: Wonder Materials ended on 25 June 2017. To find out what exhibitions and activities are open today, visit our What’s On section.

Modelling the incredibly tiny atomic scale is one of the stories explored in the Wonder Materials: Graphene and Beyond exhibition, now in its last few weeks at the museum. The star object of this section is a simple wooden model used by John Dalton to demonstrate his atomic theory, made for him by his engineer friend Peter Ewart in Manchester in about 1810. The model is part of the Museum of Science and Industry collection, and one of the most precious objects we hold. It helps us to understand how Manchester scientist John Dalton first developed his ideas about the three-dimensional structure of atoms.

The model is made up of five wooden balls, three with a diameter of 29mm, and two with a diameter of 19mm. Three are joined together, and two are loose. They were probably part of a larger group of wooden balls, and could be fitted together in different shapes to represent different chemical compounds. They are unpainted, and the grain of the wood is visible. If we examine the model closely, we can see detailed markings. We are not sure if they denote the type of atoms the balls represent, or if they are marks left behind from the process by which Peter Ewart made the model for Dalton.

Dalton was a lifelong Quaker, and was famous for his modest lifestyle. For this reason, some of his possessions were given to the Society of Friends by the family of Isabella Benson – her and her sister Hannah were Dalton’s nearest relatives at the time of his death. They were kept in Dalton Hall, a hall of residence founded by the Society of Friends in 1876. In 1957, the University of Manchester took over management of Dalton Hall and the items needed a new home. Some items remained at Dalton Hall, and a few items were given to the Science Museum in 1949, including another atomic model (museum number 1949-21). The majority of the items were gifted in 1958 by the Society of Friends to the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society. We think that our wooden model was part of this group of objects. Ownership of the model was transferred to the Museum of Science and Industry by the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society in 1997.

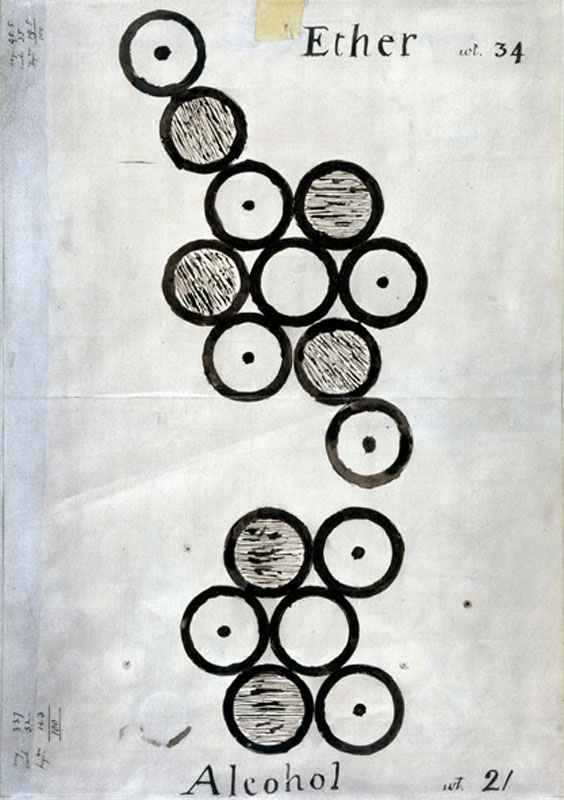

Dalton was a member and later President of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society, the first and oldest in the world. Some of Dalton’s items remained at the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society’s George Street headquarters, where unfortunately many of Dalton’s artefacts and papers were destroyed on Christmas Eve 1940 in a Second World War bombing raid. Fortunately, some items survived, and also luckily the Science Museum had made facsimiles of several of the most significant drawings fifteen years earlier in 1925, like the one below. Dalton created symbols to represent the different types of atoms, and used them to draw diagrams to represent how he thought atoms were arranged. Although the details of his diagrams were not always correct, the innovative principle of diagrammatically representing atomic structure has stood the test of time.

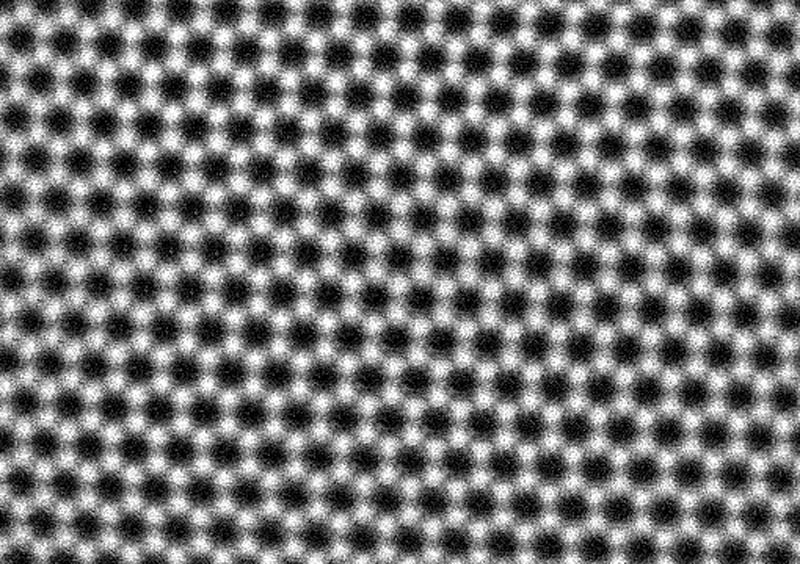

At only one atom thick, graphene is the thinnest material possible, and invisible to the naked eye. Nowadays, we can use powerful electron microscopes to zoom in and see this strange atomic world.

Image credit: Sarah Haigh, University of Manchester and Quentin Ramasse, EPSRC SuperSTEM Laboratory, Daresbury

In the Wonder Materials exhibition, we look at some of the different ways people imagined the nano-scale long before technology made it possible for us to ‘see’ atoms and how they fit together. It is clear to see the role that human imagination has played in visualising the invisible.

Image copyright: Jason Lock Photography 2016

Using his imagination, and his new theory that all atoms of a particular element are identical to each other and different from the atoms of other elements, Dalton tried to think of a way to represent atoms spatially. Dalton was a teacher by nature – he spent much of his career teaching others (including another famous Manchester scientist, James Joule), and he wanted a way to physically demonstrate his ideas to his peers and students. He was the first person to use ball-and-stick models to represent the structure of molecules. We know when and why Dalton had these models made because he describes their production and use in a letter written in 1842, two years before his death:

My friend Mr Ewart, at my suggestion, made me a number of equal balls, about an inch in diameter, about 30 years ago; they have been in use ever since, I occasionally showing them to my pupils… I had no idea at the time that the atoms were all of a bulk, but for the sake of illustration I had them made alike.

Dalton, quoted in Henry, 1854: 124

Atomic models are a tool for communicating theories and ideas, and are often used in teaching. Historian Frank Greenaway muses on Dalton’s legacy: ‘the modern successor to the balls Dalton had made by Peter Ewart still serve to link the outward with the inward eye’ (Greenaway, 1966: 223). Contemporary critics doubted Dalton’s atomic theory. Dalton’s view of the importance of thinking structurally and three-dimensionally about atoms was in fact far beyond his critics’ perceptions, and his ideas became fundamental to modern chemistry (Thackray, 1972: 115). Writing in the 1960s, W. V. Farrar said that ‘if more chemists had been playing with balls and sticks in the same way as Dalton, the world would not have had to wait so long for the theory of structure’ (Farrar, 1968: 297).

John Dalton was one of Manchester’s most talented scientists and most original thinkers. The Wonder Materials exhibition is an incredible opportunity for visitors to see his wooden atomic model from 1810 alongside objects relating to the contemporary science story of the isolation of new material graphene in Manchester in 2004. You can see Dalton’s wooden atomic model on display in the Wonder Materials exhibition until 25 June 2017. The exhibition will tour internationally until 2021.

References

Henry, William Charles (1854) Memoirs of the life and scientific researches of John Dalton. London: The Cavendish Society, p. 124.

Thackray, Arnold (1972) John Dalton; Critical Assessments of His Life and Science. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Greenaway, Frank (1966) John Dalton and the Atom. London: Heinemann.

Farrar, W. V. (1968) Dalton and Structural Chemistry in Cardwell, D. S. L. (ed.) John Dalton and the Progress of Science. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 290–298.

One comment on “Imagining atoms: A Manchester story of curiosity in chemistry”