Spherical glass lens for sunshine recorder, 1857

Made in Manchester in 1857, this sunshine recorder was clearly an act of wishful thinking by its maker.

In the spirit of getting all of the geographical jokes out of the way in the first two paragraphs, the sunshine recorder was actually invented in 1853 by a Scottish chap named John Francis Campbell, who clearly felt the appearance of sunshine in Scotland was so rare, he needed to log each occurrence.

Joking aside, it’s a fine example of an attempt to start tracking weather through scientific principles, and the development of the field of modern meteorology. The principle behind the recorder is very simple, and the technology is still in use today.

Quite what inspired the author of Celtic folklore to delve into meteorology is not really clear, but John Francis Campbell was determined to experiment with glass and sunshine.

A glass sphere sits in a wooden bowl, and as the sun blazes across the sky it burns a trace onto the bowl. The intensity and position of the burn indicate the time and strength of the sunshine, which then becomes a record of the number of hours of sunshine.

The recorder was modified in 1879 by Sir John Gabriel Stokes, who added removable paper cards behind the glass to record the burns, and changed the wooden frame to metal. Although electronic sensors mainly do the job these days, most meteorological offices and observatories around the work will still have a functioning Stokes-Campbell recorder.

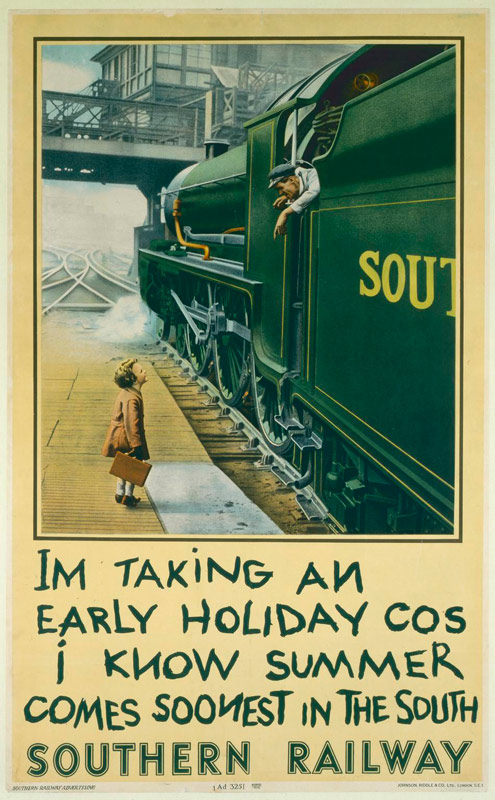

Summer comes soonest in the South poster

Likely to raise a few hackles amongst our local readers, this poster seems to suggest that it’s a bit warmer and nicer down south. Nonsense.

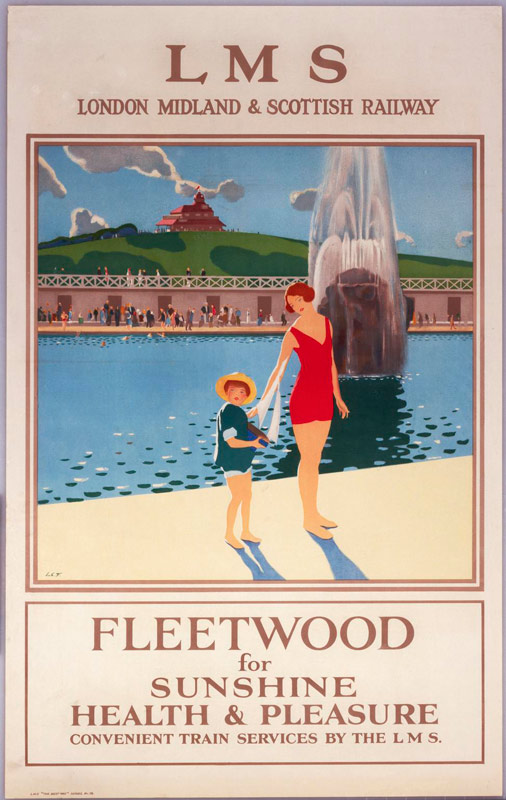

Fleetwood for Sunshine Heath & Pleasure

Sundial from Liverpool Road Station

The Liverpool Road sundial is ‘top of the pops’ in this blog post, as it’s an intrinsic part of our site and our story.

There’s a great blog piece already in existence about the sundial and the relevance of local time, featuring fascinating behind-the-scenes footage of the sundial being scanned for the BBC Civilisations project, which has turned our iconic sundial into an amazing piece of augmented reality.

However, for the sake of today’s sunshine hit parade, here’s a summary of the Liverpool Road sundial.

Made in 1833 for the Liverpool Road Station, the copper and wood sundial helped to shape the concept of time as we know it today. In the 1830s, clocks were set to local time taken from sundial readings, which meant that railway timetables had to allow for local time variations.

This practice continued until the 1840s, when railway companies campaigned for a system of ‘universal time’, presumably as they felt their customers had a right to know exactly how late they were going to be. When Parliament chose to ignore their requests, many railway companies decided to adopt ‘London time’ for their timetables.

Manchester Corporation was ahead of its time—installing a clock regulated to the time at the Greenwich Observatory in 1849. Greenwich Mean Time actually only became British standard time in 1880, when Parliament passed the Statutes (Definition of Time) Act.

Until universal London time was introduced, local times for London, Birmingham, Bristol and Manchester could differ by as much as 20 minutes. Once timetables became widespread, our national obsession with train punctuality took hold, a clock was installed at the station and the sundial became merely decorative.

Those of you who grapple with the railways on a regular basis may often feel as some operators are still working on local time variations, but that’s another story.

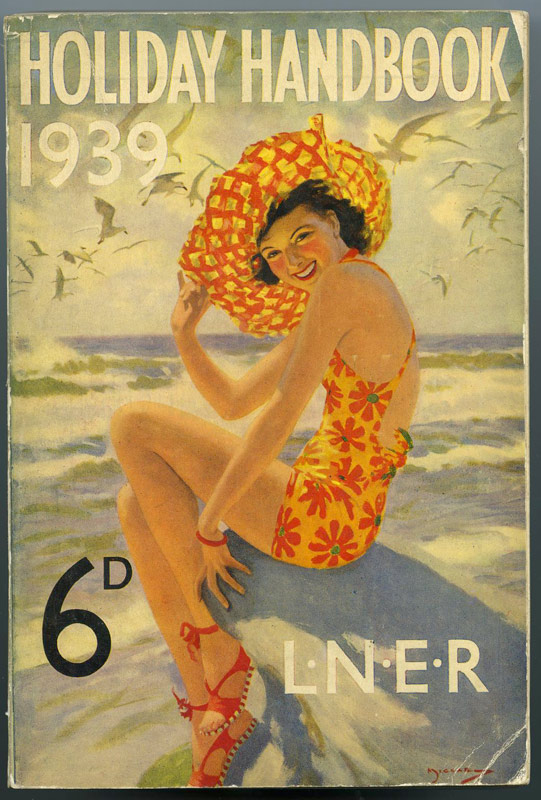

The holiday handbook 1939

What did we do before Trip Advisor? Before Teletext holidays? And before travel agents were commonplace? Why, we used the holiday handbook to help plan our adventures.

Packed with accommodation adverts, town maps and places of interest, holiday handbooks were the Lonely Planet guides of their day. Coming in at around 800 pages long, they were produced by railway companies and on sale in bookshops, or at railway agencies for around 6d. According to the National Archives currency converter tool (which is really cool and could get a little bit addictive) this is around £1.27 in today’s money. An absolute steal!

This rather fetching lady on the front of the 1939 Holiday Handbook makes me feel a bit sad, despite her becoming pose and happy smile. The handbook was produced in more innocent times before war was declared against Nazi Germany, and I can’t help but feel there were no more holiday handbooks produce after that for a while.

Please note, the author takes no responsibility for the change in the weather that will inevitably occur immediately after posting this blog online.